Search for this film on Google, and you might stumble across a striking headline: “Watching The Lobster: No Love, No Humanity?”

I think that sums up the movie’s core pretty well. Whether The Lobster truly carries that message depends on who’s watching. And since it’s all about perspective, I’ll share mine. If you’re swept up in romance or daydreaming about perfect love, I’d suggest pausing here. This piece might plant seeds of doubt and emptiness about coupledom—because maybe that’s what romantic love is: a void begging to be filled, only to stay hollow, a cycle of trust, doubt, trust again, with a lingering pinch of skepticism.

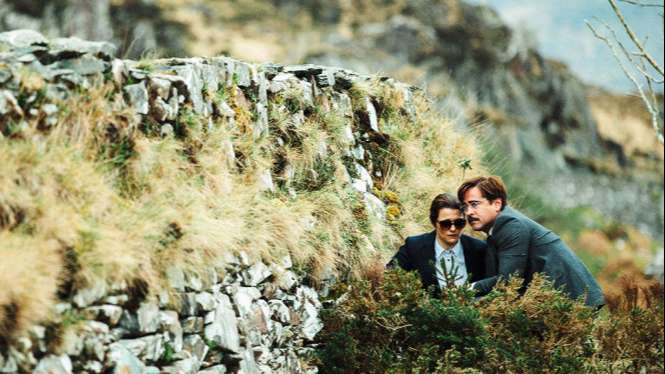

The Lobster imagines a future where citizens must pair off with partners who share their quirks (say, nosebleeds, limps, nearsightedness, or even cruelty). Singles like David, the protagonist, are hunted down and sent to a Hotel for a 45-day test. Fail to find a match, and they’re turned into animals.

“Perfect” Pairs

The Hotel deploys every tactic—enticements for coupling, threats against staying single. The unlucky singles trapped there scramble to pair up, not out of love, but survival. Love isn’t the priority, so they playact, faking similarities and harmony.

There’s a bitter irony here. In real life, when we fall for someone, we hunt for common ground—or invent it. If it’s genuine, that’s fine. But if it’s a means to an end, it’s a lie to feed personal cravings.

David and his fellow wretches claw for partners. Limping Man (characters are known by their standout traits) bashes his head to bleed, adding ketchup to snag Nosebleed Girl. David feigns cruelty to match Heartless Woman. Beyond securing a label, social approval, and physical perks, there’s no shred of humanity in them. The disjointed connection between these cold bodies chills you, twisting “love” into something primal wearing a human mask.

The film’s visuals and sounds lean on icy hues and low tones. It’s hard to believe love could bloom from such frigid hearts. Maybe just pairing up to fit society’s script and dodge singledom is enough.

Can someone without compassion truly love? Are they rushing it? Is zeroing in on one soulmate always wise? In love, isn’t “flawed but present” better than nothing?

The “Perfect” Loners

Opposing the couples, loners hide out in the Forest. I love the metaphor: the Hotel (cozy, safe, resource-rich, a gilded cage) versus the Forest (wild, harsh, but free to be yourself).

The loners have their own strict rules. They’re fanatical against romance, banning flirtation or feelings among members. Their leader enforces this harsh creed. They’re single and demand their kind live by it too.

The Hotel and Forest share one trait: forcing their beliefs on others. They fetishize their truths and demand obedience. Naturally, rigid minds don’t find wisdom, and in the end, they ruin themselves.

When the loners’ leader learns David and Nearsighted Woman catch feelings, she plots sabotage. She makes David dig his own grave and blinds Nearsighted Woman (if she’s blind, David must blind himself to pair up). They flee, and in the final scene at a city diner, David faces a choice: blind himself or not, while Nearsighted Woman waits outside.

I suspect she isn’t blind (or has healed)—she looks up to thank the waiter pouring water, then gazes out the window. A blind person wouldn’t seek eye contact. If this is a love test, it’s likely a tragedy for both.

I think I get David enough to guess his choice—he’s shown his true self through actions, not words. That self is selfish, which is human enough. Yet people still test each other in love’s game, knowing the answer might disappoint.

Romantic love is just a sliver of human affection. Elevating it to something noble takes effort and forgiveness from both sides.

Maybe that’s romantic love’s nature: a void needing filling, yet staying empty—trusting, doubting, trusting again, with a shadow of doubt.

In The Lobster, discussing love without humanity—forcing pairs to prove it or shunning it like a plague—reveals a warped, mechanical system. It mirrors a society obsessed with uniform standards, branding you human only if you fit the mold.

Ordinary folks with their biases could turn into lobsters, claws primed to shred anything different. Difference reflects free will, and freedom threatens those who cling to “normal.”

In Place of a Conclusion

I discovered The Lobster through a former student. I’ve noticed the next generation growing more independent in thought. Part of me is glad they know how they feel and what they need; part of me worries, since society might not care. Seeing life clearly sharpens you, but no gift comes free. Clarity often brings heartache.

On one hand, overpopulation, pollution, and resource depletion lack solid fixes. On the other, aging populations and pushes for marriage and kids get airtime.

Is staying single irresponsible? Must loners hide in their Forest? Should singledom be a problem, or just a choice—like any other—where you own your life?